In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte's army invaded Egypt, returning with many treasures including large numbers of Sacred Ibis mummies. The ancient Egyptians revered the ibis and mummified literally millions of them and the French naturalist Georges Cuvier used these mummies to challenge an emerging idea of the time, namely Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's theory of evolution. Cuvier detected no measurable differences between mummified Sacred Ibis and contemporary specimens of the same species. Consequently, he argued that this was evidence for the fixity of species. The Sacred Ibis debate predates the so-called ‘Great Debate’ between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and the publication of Darwin's “On the Origin of Species” five decades later. Cuvier's views and his study had a profound influence on the scientific and public perception of evolution, setting back the acceptance of evolutionary theory in Europe by decades.

Generally, animal mummies were extremely important to the people of ancient Egypt. This is clearly evident from the extraordinary number of different animal species that were mummified. Many of these mummies served as ritual offerings by pilgrims to the Gods. Of these, none are found in quantities as great as the Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus). It is estimated that four million Sacred Ibis mummies were deposited in dedicated catacombs throughout Egypt, with approximately 10,000 mummies interred each year at one site alone. Such massive numbers suggest that ancient Egyptians perhaps kept and reared Ibis on an industrial scale. There is tentative evidence in ancient writings in support of this suggestion.

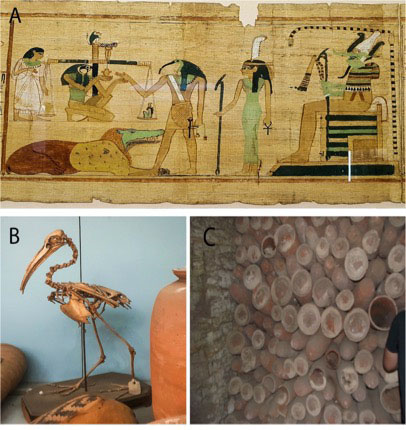

Figure 1 - Mummified Sacred Ibis. A: scene from the Books of the Dead (The Egyptian museum) showing the ibis-headed God Thoth recording the result of the final judgement. B: example of the millions of votive mummies presented as offerings by pilgrims to the God Thoth and C: Sacred Ibis mummies packed in pottery jars (from Wasef et al., 2019).

Samples were collected from Sacred Ibis remains in catacombs (Figure 1), as well as from museums worldwide. The first aim of this research was to determine if there was evidence that Sacred Ibises were farmed or even domesticated for mummification purposes. If so, we asked, is there evidence for the existence of a large central farm from which mummies were distributed to the different catacombs or were they reared in smaller enclosures? Another possibility is that locals and / or priests may have caught wild Sacred Ibises each year from migrating populations. The team showed that the ancient birds had a high level of genetic variation comparable to that identified in modern African populations. This is contrary to the suggestion in the ancient hieroglyphics (ancient writings) of centralized industrial scale farming of sacrificial birds. In addition, this research indicated sustained short-term taming of wild migratory Sacred Ibis for the ritual yearly demand.

The supply of Ibis mummies became an industry and is thought to have flourished from the Late Period, well into the Roman Period (c. 664 BC to AD 350). The HFSP researchers 14C radiocarbon dated bone, wrapping and resin samples from six Sacred Ibis mummies. These were aged between approximately 2220 and 2430 yr. BP. This suggests that most of the Ibis mummy production was from the Late Period (664 BC to 332 BC) to the Ptolemaic Period (305BC to 30AD).

We constructed DNA libraries from ancient Egyptian Sacred Ibis tissue including bone and feather (Figure 1). Second-generation shotgun sequencing of 30 ancient Sacred Ibis libraries yielded very low mitochondrial DNA content. Hence, we enriched Sacred Ibis mitochondrial sequences using DNA in-solution capture methods. Consequently, using targeted hybridisation we were able to reconstruct the first 15 complete mitochondrial genomes from ancient Egyptian sub-fossil material. Additionally, we were able to recover 26 contemporary complete mitochondrial genomes, obtained from blood and feather samples obtained from Sacred Ibis across Africa. These samples were used to estimate the genetic diversity of Sacred Ibis across the African continent and this diversity was compared with that of ancient Sacred Ibis populations. Rearing Sacred Ibises in a large centralised farm as has been suggested, might result in a low genetic variation between the mummified Sacred Ibises collected from the various catacombs. Remarkably, our results suggest that the ancient Egyptians employed an intelligent farming system that had the effect of maintaining the genetic diversity of Sacred Ibis populations.

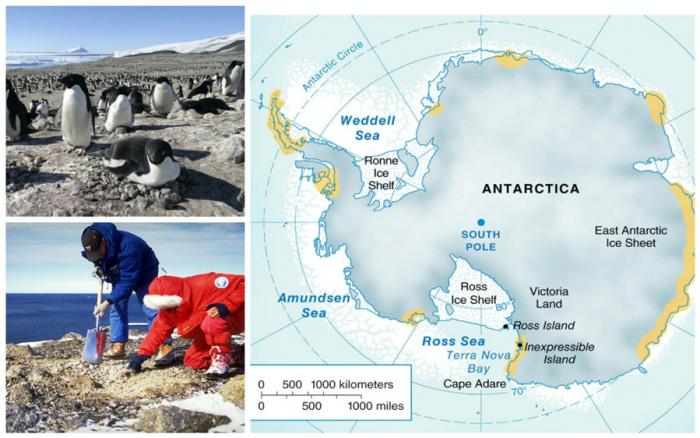

Figure 2. Adélie penguins and researchers excavating breeding sites at the Northern Cape Bird colony on Ross Island, Antarctica (from McComish et al. 2020).

We also sequenced the nuclear genomes of Adélie penguins (Figure 2) as part of our second aim that was to directly study the evolution of nuclear microsatellite alleles, also known as short-tandem repeats (STRs).

The advantage of working with Adélie penguins, rather than Sacred Ibis, is that the former enabled the team to recover ancient samples from a large number of serial time points. In addition, these samples could be radiocarbon dated up to 46,500 years compared to the much younger ages of Sacred Ibis mummies. These DNA sequences enabled us to document the patterns of change in repeat alleles and thereby to radically improve our understanding of the mutational processes that underlie their evolution.

The Human Frontier Science Program team included ancient DNA researchers, mathematicians and Egyptologists. Without the support of HFSP we would not have been able to conduct these studies. The funding was awarded to Prof David Lambert, Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Australia; Prof Eske Willerslev from the Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark; Assoc Prof Barbara Holland, School of Physical Sciences, University of Tasmania, Australia and Prof Salima Ikram from the American University in Cairo, Egypt. Dr Bennet McComish from the University of Tasmania worked with the team to conduct microsatellite evolution analyses using Adelie penguin nuclear DNA data, Caitlin Curtis worked on the recovery of nuclear DNA sequences from the Ibis, and Sally Wasef studied for her PhD in Prof Lambert’s laboratory on the mitochondrial DNA variation. In relation to both projects the team collaborated closely with Assoc. Prof Craig Millar from the University of Auckland.