In our recently published study, we use novel microfluidic experiments, mechanistic models, and evolutionary game theory to show that bacteria living in these porous environments face a fundamental dilemma. In porous environments cells rely on flow for nutrients and dispersal, however, as they grow they tend to reduce their access to flow, diverting it instead to competitors. The interaction between biofilms and flow can thus select for bacteria that grow more slowly, which stands in sharp contrast with classical theory. These new insights may give us the tools to rationally engineer microbial communities for important functions, like cleaning up polluted groundwater or enhancing oil extraction.

For the full story see the press release from the University of Sheffield

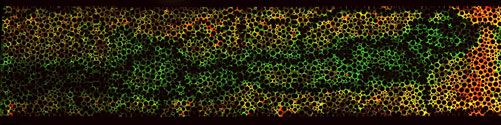

Figure: Two different types of bacteria, one labeled red and the other green, compete in a microfluidic device that simulates soil (credit: Katharine Coyte, Roman Stocker, and William Durham).

Reference

Microbial competition in porous environments can select against rapid biofilm growth. Coyte KZ, Tabuteau H, Gaffney EA, Foster KR, Durham WM. (2016). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. E161-E170.