The mammalian gut is home to a tremendous number of microorganisms, termed the gut microbiota. This peaceful community helps to digest complex carbohydrate, such as dietary fibers, and provides the body with important nutrients and other molecules. At the same time, however, this bacterial community may become a danger to the body when it is not safely contained in the intestine. Thus, to separate the gut bacterial community from the body, the intestinal surface is covered with a mucus layer, which acts as a physical barrier that keeps the gut bacteria at a good distance from the gut wall.

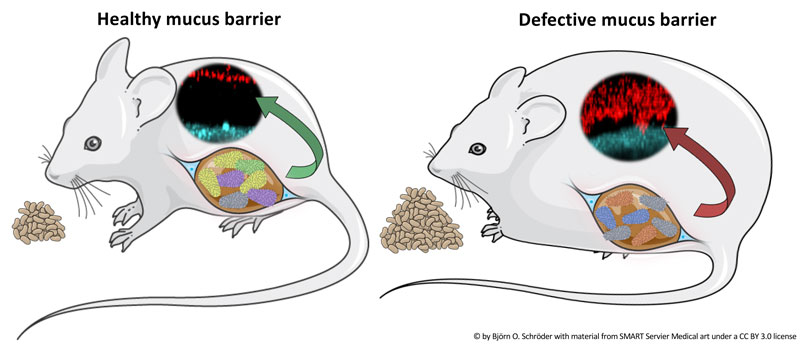

Figure: Lean mice have a healthy intestinal mucus layer that is not penetrable to bacteria or bacteria-sized beads (left image). Genetically obese mice that overfeed on the same diet, due to a missing satiety hormone leptin, have a penetrable mucus layer, allowing bacteria and beads to come closer to the intestinal epithelium, which increases the risk of infection (right).

The intestinal mucus layer has long been considered to be a simple lubricator to facilitate passage of the fecal material through the intestinal channel. Only in recent years has it been understood that the structure and function of the mucus layer are dependend on the presence of gut bactria, of which some bacteria are more important than others.

Previous research found defects in the mucus layer in mice that were fed a diet that lacked dietary fibers, a so-called 'western-style' diet. Under these conditions, it is thought that the gut microbiota start chewing on the plentiful carbohydrates that are present in the mucus shield. The study of Schröder et al., however, shows that mucus defects can occur even under a fiber-rich diet. By using a unique measurement system, they found that genetically obese mice, which over-eat this fiber-rich diet, have a defective colonic mucus layer with increased mucus penetrability and a strongly reduced ‘mucus growth rate’. Furthermore, their data suggest that the gut microbiota community of obese mice may cause these colonic mucus defects, even in the presence of dietary fiber. Yet, it is so far unknown whether the gut microbiota may have similar effects in obese humans as well.

The HFSP Fellowship allowed me to change my research focus from biochemical work on antimicrobial peptides to work on gut microbiota, metabolism and mucus. At that time it was a risky approach, as almost nothing was known about this complex interaction in the gut. Yet, now this interaction is well appreciated and the HFSP Fellowship layed the groundwork to develop my own independent research at The Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine Sweden (MIMS) in Umeå, where I will combine research on antimicrobial peptides and mucus and their interaction with the gut microbiota.