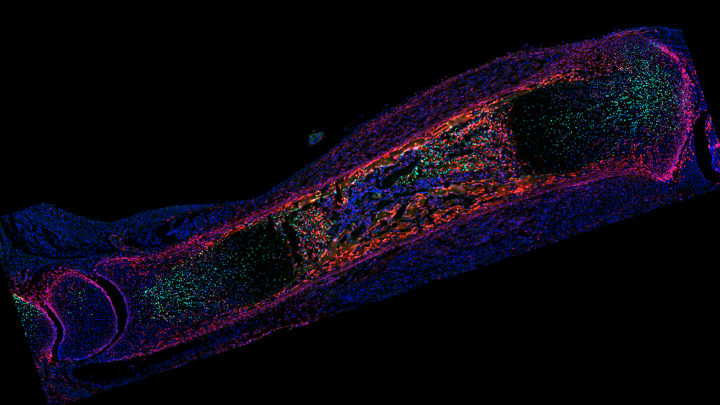

Long bones in the limbs grow via a cartilage template that is progressively replaced by bone. In mice, cartilage progenitors show a postnatal switch of behaviour, from being short-lived to being self-renewing, long-lived cartilage progenitors (LLCPs). A big question in the field is which cells in the fetal limb are precursors of LLCPs, and when/how LLCPs are generated. In this study, the HFSP Career Development Award recipient Alberto Rosello-Diez and his team start to provide an answer, showing that cells that express the transcription factor GLI1 are the fetal precursors of postnatal LLCPs, and that Gli1+ LLCP precursors remain mostly dormant until postnatal stages.

However, in response to genetic inhibition of cell proliferation in fetal cartilage, the descendants of Gli1+ cells dramatically increase their numbers in the cartilage, compensating for the perturbation and enabling normal growth. Specific elimination of the cartilage cells (but not other cell types) derived from Gli1+ precursors precludes the compensation for the genetic inhibition of cell proliferation.

The HFSP Awardee further shows that some reparative Gli1+ cells originate from Pdgfra+ cells located outside the cartilage, revealing the surrounding tissues as a source of back-up cartilage progenitors when needed. While the exact process of conversion and/or migration from non-cartilage Pdgfra+ cells (P) to Gli1+ cartilage cells (G) has not been completely elucidated, it seems to involve a self-regulating mechanism. If the cartilage is growing well, it produces a substance that blocks the P-to-G conversion. If growth falters, however, that substance is produced at lower levels, lifting the brakes on the P-to-G conversion.

While several new questions have been raised by this study, it sheds light on the long-standing question of the origin and regulation of LLCPs, laying the groundwork for future approaches to stimulate the in vivo production of cartilage-reparative cells to treat congenital or acquired growth disorders.